|

Why can't you correct room acoustics with

electronics?

Use of sophisticated (and expensive)

equalization to attempt room correction made the

rounds of sound reinforcement companies and

recording studios in the sixties and seventies.

It’s now back (times five or more ) in home

theater rooms. While equalization can make a

good system sound even better in a good room, it

does not re-write the laws of physics.

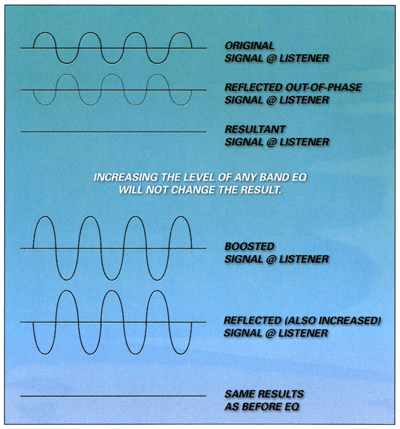

The room is an active environment. It will fight

back in what we’ll call an acoustic “Zero Sum”

game: increasing the power of the absent

frequency also increases the level of the

out-of-phase room reflection, perpetuating the

“null” in the room.

It may even be possible broaden it. Remember if

the sum of the +3dB SPL original and –3 dB SPL

reflection equals zero, so too will adding 3 dB

for a + 6 dB original SPL and – 6 dB reflection

SPL sum to zero.

This can be demonstrated effectively with a

simple science experiment: Using a single driver

loudspeaker, a single frequency oscillator, and

an amplifier, feed a 1000 Hz tone to the speaker

through the amplifier to achieve a comfortable

listening level. Reposition the speaker to face

a hard, flat surface approximately 6-3/4 inches

away. The sound will all but disappear.

Click Here to see a video demonstration of this

experiment.

This is due to the distance being one half

wavelength of 1000 Hz. The reflected energy is

180 degrees out-of-phase with the source. The is

most easily shown graphically:

Increasing the source signal level will always

cause a corresponding increase in the reflected

signal level. In practice, the reflected signal

is going to be slightly less and some sound will

be heard as signal strength will diminish over

distance and absorption.

Footnote: Sound travels at approximately 1130

feet per second in air.

The wavelength of 1000 Hz is 1130 feet divided

by 1000 Hz equals 1.13 feet. Half wavelength is

1.13 feet, which divided by 2 times 12 inches

per foot equals 6.78 inches. This calculation

will vary slightly for temperature, pressure

(altitude) and humidity conditions.

Haven’t we passed this way before?

During the days of increasing playback channels

(mono, stereo, quad) and increasing recording

tracks (mono, two track, three track, four

track, eight track, twelve track, sixteen track,

twenty four track) there was also an increasing

awareness of acoustics. Why did the mix sound

different at home or in the car not to mention

in the next studio? The authors have seen rooms

vary 12 dB within the same facility with mixes

being all bass or no bass depending upon the

room in which they started.

When these rooms were corrected with

equalization, it typically covered only the

mixing engineer’s position or “sweet spot”. Some

complained of having to wear a neck brace for

fear of falling out of the sweet spot. Of

course, the producer, needing to hear the same

mix would literally be in the engineer’s lap,

and, if the artist and musicians came in to

listen, not only would they not hear the “real”

mix, they changed the acoustics of the room by

being there.

Adding or subtracting by equalizing induces

phase shift and “ringing” due to deteriorating

quality. The equalization curve is bell shaped.

Increasing “EQ” broadens the effect to the

nearby frequencies as well as the offending one,

creating a situation requiring further

correction. A narrow “high Q” equalizer may

overcome this but introduce its own problems

such as phase shift. An equalized boost or cut

doesn’t change the resonance of the room, it can

only “correct” an idealized sweet spot.

With the new range of room equalizers averaging

around $10,000 the serious audiophile is wise to

consider as little as one-third of that amount

to acoustically treat the room. A two-inch panel

of 7 pound per cubic foot fiberglass will

effectively eliminate reflections above 500 Hz

and also reduce the problems by 45 to 75 percent

in the two octaves below that point. It will

allow the “upscale” equalizer to do its job (or

possibly eliminate the need for it). The sweet

spot will be widened.

What is the ideal room?

We often read about the “ideal” room. Ideal

would seem to imply a unique right way of doing

something. However, there are several ideal

rooms.

“Ideal” Room Ratios (set up for equal ceiling

height)

|

Harmonic

Vern Knudsen

European

J. Volkmann

P. E. Satsine

Golden Section |

1: 2.00: 3.00

1: 1.88: 2.50

1: 1.67: 2.67

1: 1.60: 2.50

1: 1.50: 2.50

1: 1.62: 2.62 |

The harmonic is least desirable because of its

coincident reinforcement of normal room modes

resulting in a series of tones. To refute this,

all one has to do is enter the room to alter its

acoustic properties, add more furniture, etc.

Every room will have “modes”. The real design

criteria is to have “many” and spaced closely

together. The lowest natural room frequency is

typically the axial mode (length, or longest

dimension) and is determined by the following

formula:

(Frequency) f = c/2L = 1130/2L,

Where C = speed of sound (1130 feet per second

in air); L = room length

Conclusion: It is unfair to judge any piece of

audio gear in a room that fights back. Fixing a

room with an equalizer is only one of many audio

myths. Correct the acoustics first and all of

the equipment, including the equalizer, will

have a chance to live up to its published

potential.

Nick Colleran is a principal in Acoustics First

Corporation and a former president of the

Society of Professional Audio Recording Services

(SPARS).

John Gardner is an acoustical consultant who has

designed and built professional recording and

theatrical facilities throughout the world.

|